Which changing baseline do you think of when viewing the above photo? Forest type, snow pack, fire regime?

The world I grew up in differs from yours, just as it differs from that of my parents, and it will be different for my children. This is not too bold of a claim to make. The progress of technology is exponential and, in my lifetime, I have experienced three tech booms: the adoption of the internet, adoption of cell phones and now, the release of AI. Technology is a measure of change, there are rarely more VCRs, Walkman’s, eight tracks, you name it, but how does change measure up in nature?

Natural change is not always apparent over long periods, or even across generations. The forests I know will be different than the generation pre-or-proceeding me. Historical forests were indeed ancient, tracts of land that had not been accessible to modern machines, that is no longer the case. For example, only an estimated three percent of the inland temperate rainforest of British Columbia remains. Unfortunately, it still is being harvested. UNBC released an article stating that if changes aren’t made, there is a risk of ecosystem collapse in 9 to 18 years. What scenario can you think of where three percent, or less than 20 years away, is not considered “in grave jeopardy” when relating to something that can’t be financially replaced, nor even regrown in the lifetime of five generations? Unfortunate as it is, I believe that it is normalized. There is a concept called “Shifting Baseline Syndrome” which applies here.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome

Shifting Baseline Syndrome, SBS, first coined in 1969 by Ian McHarg, is the change in how a system is measured against itself, especially when measuring against a previous generations' reference points of the same ecosystem. So what does that mean?

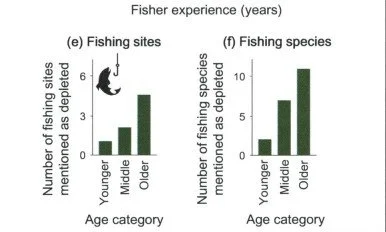

The above figure is from Soga, Gaston, & Halsey 2018 and explains the shift in baselines over generations. In this particular example, it is referencing Japan’s forest composition. This could easily be seen as a metaphor for Canada as well.

“With ongoing environmental degradation at local, regional, and global scales, people's accepted thresholds for environmental conditions are continually being lowered. In the absence of past information or experience with historical conditions, members of each new generation accept the situation in which they were raised as being normal.” - Masashi Soga & Kevin Gaston

Shifting Baseline Syndrome is a sociological and psychological issue. Several examples of anecdotal evidence have reached my ears from older generations as I was growing up in a rural community, and, stereotypically, they would all begin with “There used to be…”.

….so many salmon

….a lot more elk

….trucks with just one log coming through town every week

Another illustration from Soga, Gaston, & Halsey 2018. When old timers say that “it ain’t what it used to be”….they’re not wrong.

Those are examples that were common to me in my tiny corner of the world. Fortunately, someone, somewhere, has sounded the alarm on an international scale and efforts to protect and restore salmon and elk populations as well as forests are in effect on local, provincial, state, and national levels.

This previous summer, I heard from kids visiting Toronto from British Columbia who said “It’s smokey just like home during the summer”. Meaning that summers are not only associated with fun, bike rides, camping, etc, but also smoke from wildfires. It’s the new baseline.

Consequences of SBS are subtle until the subject at hand collapses. How are we to know the state of a population is five percent of historical value when we have only been exposed to the five percent population and deemed it “normal”?

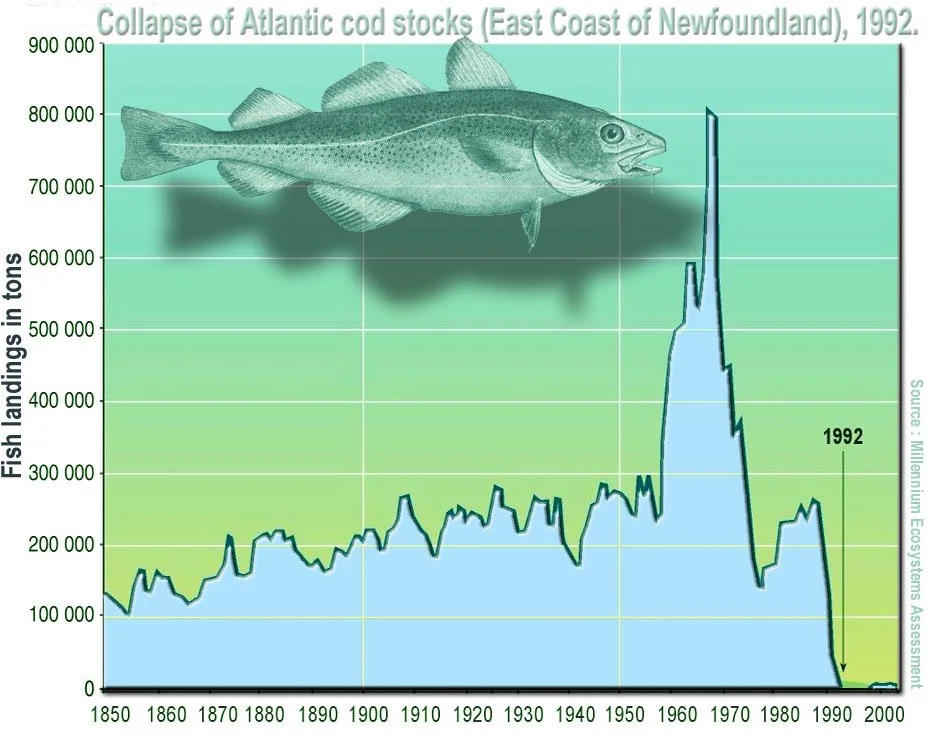

Newfoundland, an eastern maritime province, has a textbook experience with Shifting Baseline Syndrome and poor management of resources. In 1992, following several decades of overfishing, the cod fishery which was the identity and primary income for coastal communities, collapsed. It was an overnight event, on July 2, 1992, a moratorium on cod fishing was announced, decimating coastal communities. The moratorium caused over 35,000 jobs to be lost in a single statement.

This figure shows the cod fish catch in tons, which can be directly related to the population of the fishery. The 60’s had their heyday, 30 years later, collapse. Source.

I write that in a bad light as if the moratorium was a poor decision. But was it? The fishery was decimated. Today the fishery is still in recovery.

The issue of shifting baselines is an ecosystem-level topic, generally dealing with populations or large areas and we as humans are intrinsically linked to this phenomenon. I believe that it is not our human intention to destroy ecosystems or populations, at least many years ago, before we knew of the potential damages caused by our activities, but perhaps it is a display of our wider grasp on understanding the fundamentals and connectedness of nature.

“Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

How do we, as a society, justify the repetition of damaging ecosystem health and populations? We certainly could at one point plead ignorance, but we can no longer do that with our contemporary knowledge. Are we not confronting the truth about our species, all species, that for survival and propagation, other species must die?

Where does the issue lie?

Normalization of Deviance.

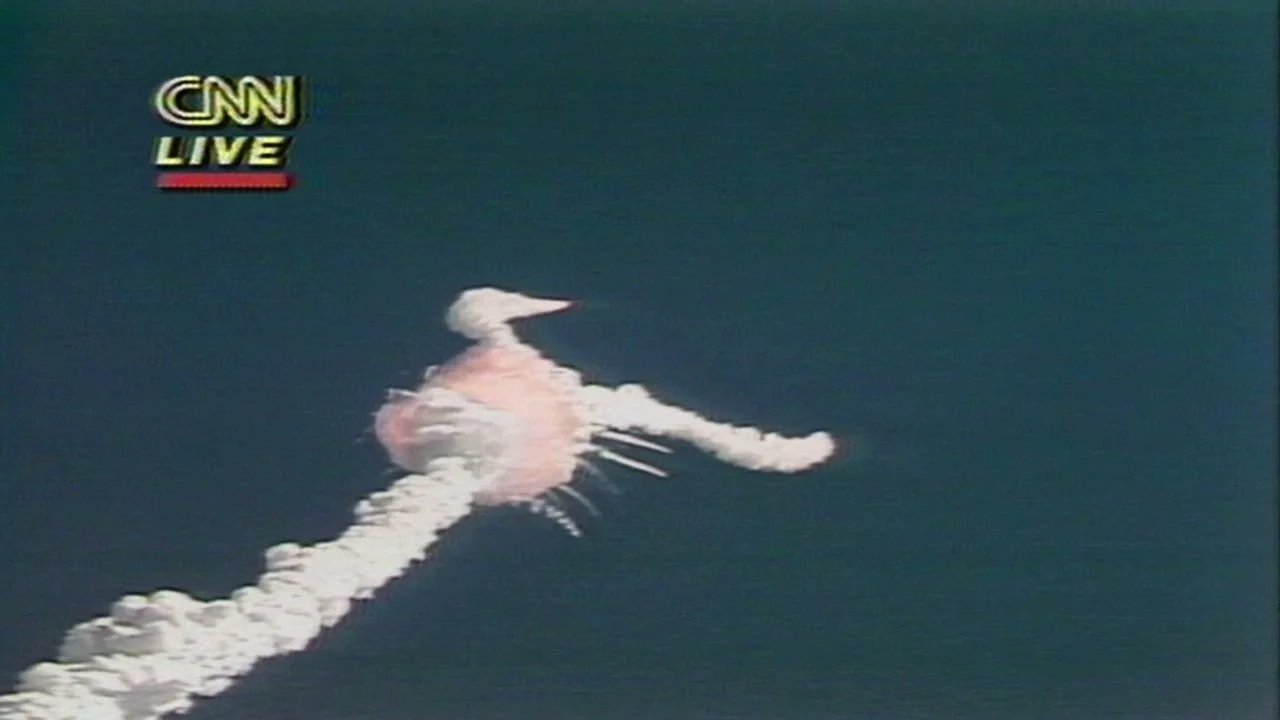

The Space shuttle Challenger destroyed mid-flight on live television due to a known and preventable error. The Normalization of Deviance in this situation cost seven astronauts their lives. Source.

A term coined not long ago by Diane Vaughan in relation to the Challenger Disaster, the NASA space shuttle that exploded 73 seconds after launch in 1986. It is a term that is gaining popularity and can exhibit the adage “poor practice = poor performance”.

The normalization of deviance is similar to Shifting Baseline Syndrome in the sense that there is a shift away from what we think of as “normal” to a new version of “normal”. Both terms are typically used in a negative sense, that the shift away from “normal” occurs not towards the positive, or better, but towards a worsening environment. This issue compounds itself by repetition, a positive feedback loop, deviating further and further from the original baseline or “normal”. The habit deviation then becomes ingrained in the culture and, therefore normalized.

(A three-part video that explains the Challenger explosion and its relationship to the Normalization of Deviance)

Examples of this in society on the day-to-day scale are plentiful, one of the most worrisome examples being the speed limit in Ontario. Did you know, that driving an excess of 20 km/h over the speed limit is normal? No joke! How did that offense get to become normal? Surely it was over time, that the new “normal” speed crept its way up and up to reach the point where it is today. It’s a cultural norm.

Southwest Ontario is a consumer, dog-eat-dog, fast-paced culture where peoples’ pride is associated with the objectivity of their material items over the condition of their natural resources. Everyone is in a hurry, horns blare at stoplights, politeness is overshadowed by personal urgency, and quality has lost out to speed. Normalization of Deviance has played a pivotal role in the shift of culture, for the normal now has surely strayed.

It is within our day-to-day lives that we consciously, or subconsciously, foster this deviance. “Just a little faster…”, “Just a little more…”, “It’ll be fine without…”. This ideology is normalized and spread through society, to the youth, who inevitably will deviate further from the baseline of their parents. Where is it that we draw the line and return from deviation?

I do realize that to some I may sound like a curmudgeon, but where do we draw the line? Where do we put our foot down and say “enough is enough”? Do we do it before another ecosystem collapses? Do we do it before the preventable death in a speeding accident?

These are the questions to which we must hold ourselves accountable. When do we reflect on our “progress” and realize that what has been done is harmful? I’m all for change, but it need not be change due to lack of integrity, instead, change due to the promotion of positive, well-thought values.